In the mind of every kidney disease patient, starting from the day of his diagnosis, a question lingers on like an unsolved puzzle—“Whether I will need dialysis” and, if yes, “when do I need dialysis.”

Let me tell you one thing point blank, for that’s what it is. Even though it remains the most fearful aspect of kidney disease, only a handful of CKD patients will ever need dialysis. Look at these numbers, coming from the United States, no less. Roughly thirty-Seven million people in the United States have CKD, yet, only about 0.6 million are currently on dialysis.

Despite these encouraging numbers, one would still like to determine how likely it is that one would need dialysis in the future. As your kidney disease inch toward complete failure, four main factors determine when you need dialysis.

Age—How Old Are You?

Age has a significant bearing on your chances of needing dialysis; as you get older, your likelihood of going on dialysis decreases. After analysis of the data, doctors have formed two conjectures. First, older patients lose kidney function more slowly than younger patients, primarily due to low protein levels in the urine. Not surprisingly, many studies have shown stable kidney function in older patients for years, decreasing the likelihood of going on dialysis with increasing age. Then, older patients have other illnesses that may claim their lives before ever needing dialysis. Remember, no one lives forever.

Of note, for our purpose, old age means seventy or above.

Loss of Kidney Function Over Time—Plotting Your eGFR

During a patient visit, I always spend a major part of the encounter educating the patient about their eGFR (estimated glomerular filtration rate). This effort is worth the time because learning about one’s eGFR brings several benefits. It alleviates patient anxieties. It helps patients better understand and even control their kidney disease, for they now have a metric toward which they aim all their efforts for a healthy kidney. Third, it takes away uncertainty and brings a sense of control, like we feel when we have GPS on long road trips.

If you measure eGFR on every visit to your kidney doctor, usually four times a year, you can plot the progression of kidney disease. Plotting eGFR helps in two ways. First, since eGFR fluctuates a lot with minor changes in creatinine level, you learn with time to value only the average amount of eGFR, not the fluctuations. Next, plotting allows you to measure the eGFR you are losing per year. And this number is essential, for this loss of eGFR per year defines the rate of kidney function loss.

For example, if a patient’s eGFR was 60 ml/min at the start of 2013 and went down to 30 ml/min in early 2018, he lost 30 units in the five years, which means he has been losing an average of 5 units every year.

How much are you supposed to lose if you manage your kidney disease well?

An average healthy person loses less than 1 ml/min of eGFR annually. As a CKD patient, however, if you lose less than two units per year, you have a slow loss of kidney function. Loss of eGFR between 3 to 5 units per year is considered a little fast. Losing more than five units per year means a rapid decline in kidney function—bad news.

Simply put, plotting eGFR allows a broader view of the speed with which you are headed toward dialysis. But are there more precise methods to calculate this probability?

Predicting the Need For Dialysis—Kidney Failure Risk Equation

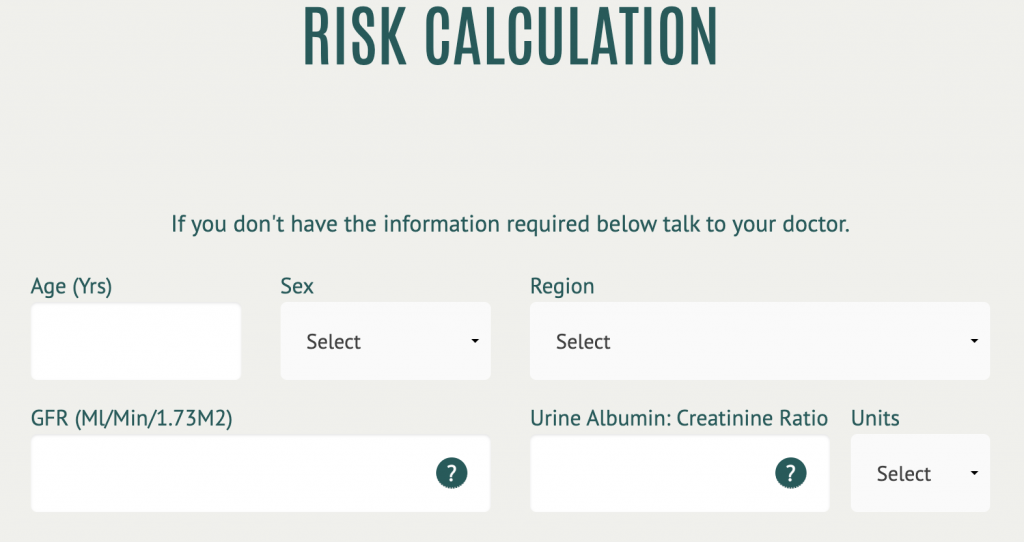

The kidney failure risk equation is a decent tool that nephrologists use to predict whether a patient will need dialysis in the near future. The equation uses four variables—age, gender, eGFR, and urine albumin/Cr ratio—to predict the 2 and 5 years probability of needing dialysis in a treated kidney failure patient.

For example, a sixty-year-old female with eGFR 30 and urine protein of 30mg/g has a 7.5 percent risk at five years, which means she has a seven out of a one hundred chance of needing dialysis in the next five years.

Among these four variables, the most important is the urine protein, much more than other variables in skewing the risk toward dialysis. This heightened risk is why your doctor always focuses on your urine protein and tries to reduce this number.

This equation is available at www.kidneyfailurerisk.com, but I always prefer that patients use it in the presence of their doctor, for their scores can trigger many questions and concerns.

Note: This equation also has a variant with eight variables for more accurate scores, but most nephrologists use the four-variable version, for it requires less blood work, which avoids unnecessary delays.

Dialysis Vs. Death

Dialysis is a life-saving procedure; many patients live on dialysis for years. Still, dialysis is considered a grim prospect in almost all cultures, at least as long as a patient remains in a state of denial. No wonder, when the subject of dialysis is approached, I find many patients saying, “ I would rather die than go on dialysis.” In the past, we used to look at such pessimistic conversations as a part of denial or depression. However, this patient perspective has recently gained more respect and attention, so much so that a slew of literature is now available for nephrologists to manage their patients conservatively, meaning taking care of end-stage-kidney-failure patients who need dialysis but want to live without it.

Usually, such thoughts dominate the minds of patients with eGFR below 30 ml/min, patients who frequently have to hear about dialysis during doctor visits. For these patients, there exists an even more advanced CKD risk assessment tool called “Timing of Clinical Outcomes in CKD with Severely Decreased GFR.” This online equation, available at www.ckdpcrisk.org, takes nine variables—age, gender, race, eGFR, systolic blood pressure, history of heart disease and diabetes, urine protein, and smoking history—and gives your not two, not four, not even six, but the probability of nine outcomes at the end of two- and four-years. At any rate, it answers two most burning questions for an older patient with failing kidneys: the risk of needing dialysis and the likelihood of dying of a non-kidney-failure issue before requiring dialysis.

When to Start Dialysis—Early or Late

At what eGFR you start dialysis makes a huge impact on predicting your time to start dialysis. Let me explain. Assume, for instance, a patient whose eGFR just hit 30 and he crossed over to stage 4 of CKD, and the patient’s kidney function is declining rapidly, losing five units every year. If the patient’s team decides to start dialysis at eGFR fifteen, he has three years before starting dialysis. But if dialysis is started at eGFR 5, the recommended time to start dialysis, he would have five years without dialysis.

Here it is important to remember that we prefer to defer dialysis as long as possible, for starting dialysis earlier has shown no benefits but rather some bad outcomes.

Unseen event—AKI

We have now learned that most kidney disease patients with stages 1, 2, or 3 are unlikely ever to reach the point of dialysis. There is an exception, nevertheless—acute kidney injury. Sometimes these pretty stable early-stage CKD patients get too sick or show a bad reaction to a drug, developing somehow a complete kidney shutdown that dialysis. However, almost all these patients recover from the episode, rarely needing life-long dialysis if the cause of AKI is recognized and treated promptly. Therefore, for all patients who have normal kidney function or eGFR above 30 and have had to start dialysis, you must ask your kidney team to keep checking for the return of your kidney function.