Kidney disease is a worrisome condition, and in some forms, it can turn a patient’s life into a toiling existence. Chronic kidney disease shares its debilitating features with four other chronic conditions—congestive heart failure, cerebrovascular accident (stroke), obstructive lung disease (COPD), and chronic liver disease (CLD)—a group notoriously called 5 Cs of medicine. Among this group, however, kidney disease is the most daunting of the five illnesses, for once diagnosed with kidney disease, a patient’s mind fills with thoughts about dialysis. No doubt, chronic kidney disease does have a bleak side, and the fears surrounding it are real, yet there is a lot we can do for patients with kidney disease. It seems that the subject has not been properly discussed.

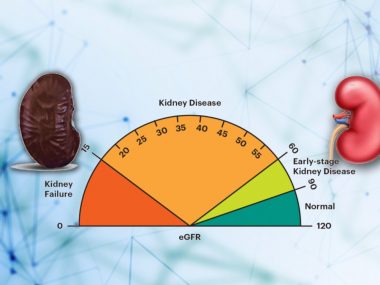

Kidney Disease is a common medical condition. Roughly one out of every ten people carry some disturbance in kidney function or structure. Usually, such minor changes remain undetected for a long period basically for two major reasons. First, kidney disease is a painless process. Second, we lack guidelines for screening the general population for kidney disease. This gap in guidelines is due to three main reasons: insufficient evidence of any benefit from early detection of the kidney disease; unknown cost-effectiveness, which means that we don’t know if doing so is worth it; and poorly understood risk-benefit profile with the management of the chronic kidney disease in its early stages, which means that by treating the kidney disease in its early stages we may cause more damage than good.

Surprisingly, this reluctance in screening disappears in some instances, particularly for patients with conditions that increase the chances of developing kidney disease— such as diabetes, hypertension, a family history of kidney disease, or acute kidney injury, to give a partial list. We have clear guidelines for screening kidney disease in such groups, mainly because of two factors: their higher potential for developing kidney disease, and there is something we can treat.

Efforts to detect kidney disease early in such patients have led to the development of new screening methods. One such emerging concept in screening is that of kidney injury markers. These tests, usually from a urine sample, seek to highlight kidney breakdown products, indicating not only the kidney disease but also the specific part of the kidney that is being damaged. Another method includes genetic profiling, a study of genes to identify the possible kidney disease way earlier than the traditional tests, like creatinine and urea, can do.

This accuracy in early detection is not without concerns, though. With such powerful tools, physicians may predict kidney disease long before its overt appearance, but for patients, it may result in unnecessary anxiety. And patients have a reason for this apprehension because the diagnosis of kidney disease translates itself into dialysis on the community level. The misconception carries even stronger emotional appeal in developing countries, where the kidney disease-dialysis connection seems as true as it can get, the main reason being late diagnosis and poor management. Regarding dialysis, the fear is real, for no matter how you go about it, the procedure draws a big chunk of quality time out of patients’ lives.

However, before going to transplant or dialysis, we have an array of options to treat kidney disease, and by the year, prospects are getting better. Now we have new drugs with more efficacy and better side-effect profile. The introduction of three medicines, recently added to the nephrology shelf, would suffice for our purpose. With an incredible safety profile, new potassium binders allow nephrologists to use some renal protective medicines to their maximum potential, drugs that we were unable to use at their maximum dose, concerned, as we were, with the risk of raising potassium to fatal levels. Another new class of drugs is flozin—apparently, a magic pill with jaw-dropping benefits in kidney patients. Besides their promising results, these drugs mimic the effects of at least three medicines, promising a decrease in the pill burden.

Dialysis, too, is no less magic. Here, too, kidney disease has a bright side—the kidney is the only organ for which we have a replacement therapy in the form of dialysis. For other organs, such as the heart, liver, and lungs, there are no machine substitutes, at least not to a great extent and not for the long term. We do have the option of transplant for some organs—heart, liver, and lung—but a strict eligibility criterion makes it hard for most patients to be eligible. As a result, the number of these organ transplants is minimal, much less than kidney transplants.

According to united network for organ sharing (UNOS), a non-profit with a federal contract for coordinating the countries organ procurement and transplant efforts, the most common organ transplant in 2019 was kidney (23,401), followed by liver(8,896), heart(3,551), and lung(2,714).

Lastly, we have more data regarding the effects of lifestyle modification on kidney disease: Balanced nutrition, regular exercise, and adequate sleep are as essential for kidney health as medicines.

In short, chronic kidney disease is a chronic and irreversible condition, which affects all other organs and is, naturally, affected by other organs, for the kidney remains in constant crosstalk with the rest of the body. Early detection and targeted management are keys to reducing the burden and progression of kidney disease. Once detected, nephrologists and the health care team can play a significant role in keeping the patients from dialysis using precision medicine.

When the disease reaches the last stage, a smooth transition to dialysis or bypass to transplant should be the goal. Remember that a healthy lifestyle—diet, exercise, sleep—plays a more critical role in kidney health than we previously thought. Learn to live well with kidney disease.