Diabetes accounts for more cases of CKD (Chronic kidney disease) than any other disease. Forty-four out of every hundred kidney disease patients develop the condition secondary to diabetes. Diabetes carries certain inherent characteristics that lead to structural changes in the kidney’s blood vessels, resulting in higher pressure in these vessels that ultimately leads to CKD. The risk of developing kidney disease in diabetic patients runs so high that one in every three diabetics finally gets CKD.

The risk of developing kidney disease in diabetic patients runs so high that one in every three diabetics finally gets CKD.

Once a patient develops diabetic kidney disease, the journey beyond this point is not decent, either. Many of these patients wind up with end-stage renal disease, requiring dialysis, the incidence of which is, surprisingly, on the rise, despite all the improvements in the treatment of diabetes and diabetic kidney disease.

However, we have means to manage diabetic kidney disease, which, if followed religiously, can significantly reduce the risk of complications.

Types of Diabetes

To better understand diabetic kidney disease, we first need to learn about the types of diabetes. Broadly speaking, there are two main types of diabetes. Type 1 diabetes occurs due to damage to the pancreas, which then becomes unable to secrete a normal amount of insulin. In Type 2 diabetes, there is no structural damage to the pancreas, and it does produces insulin, but either the amount of secreted insulin is not enough, or the body has become resistant to insulin, requiring higher levels of insulin to function.

Most diabetic kidney disease results from type 2 diabetes. This preference of CKD for type 2 diabetes turns out to be logical when you look at the natural course of both types of diabetes.

Type 1 diabetes manifests itself as soon as the pancreas fails to secrete insulin. The insulin essentially disappears from the body, blood sugar spikes to an alarming level, the patient ends up in the emergency department.

Type 2 diabetes, on the other hand, can be present for many years before revealing the symptoms, exposing various organs, in the meantime, to the damage caused by insulin resistance and slightly elevated blood glucose. This subclinical commotion continues until the pancreas gives up, unable to keep up with the body’s increasing need for insulin. As a result, blood sugar levels stay persistently in the diabetic range, producing typical symptoms of diabetes, such as dry mouth, frequent urination, and weight loss.

All this means that Type 1 diabetes patients get diagnosed right after damage to the pancreas. In contrast, type 2 diabetes, where the pancreas winds up gradually, may show a lag of many years between the onset of the disease and its diagnosis. This difference in the natural course of the two types of diabetes also accounts for the difference in guidelines for screening diabetic kidney disease, as we will discuss in a minute.

Diabetes to Diabetic Kidney Disease

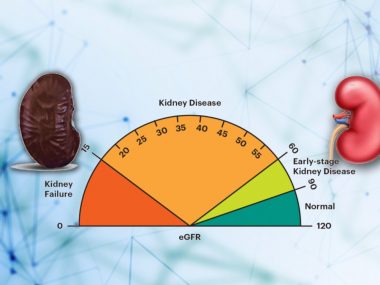

Diabetic kidney disease results from damage to the tiny blood vessels in the kidney, making them leaky to the proteins. Put simply, If you have diabetes and you spill proteins in the urine, you may have diabetic kidney disease. So how do you check proteins in the urine? Screening for diabetes requires a simple urine test called a urine dipstick. If this preliminary test turns out positive, your doctor orders a more specific urine test called Albumin, Creatine ratio, a test that tells your doctor the exact amount of proteins you are spilling in the urine.

Labs report urine protein in three main groups: Below 30, 30 to 300, and more than 300. If urine protein is under 30, you have normal protein in the urine. If it is between 30 and 300, you have mildly increased protein in the urine. This needs to be looked at and managed accordingly. Finally, if you have a protein of more than 300, you have significant proteinuria.

Guidelines for kidney disease screening in diabetic patients differ in type 1 and type 2 diabetes based on their distinct natural course. For type 1 diabetes, it is recommended to start screening five years after the diagnosis and then annually. In patients with type 2 diabetes, screening should start right after diagnosis of diabetes and then annually. Note that this annual screening is for those patients who test negative for urine proteins; patient whose urine show protein require more frequent evaluation after the first positive test.

Protein in the urine signals the start of blood vessel damage in the kidney, the hallmark of diabetic kidney disease. Once detected, this marker calls for stricter measures to stem the progression of kidney disease.

Diabetic Kidney Disease Management

Typically, diabetic kidney disease patients are more likely to have a progression of kidney disease and heart conditions. However, we can reduce this risk and manage diabetic kidney disease by regulating multiple parameters simultaneously. All these measures are equally important.

Control Your Blood Sugar

Controlling blood sugar levels forms the foundation of diabetic kidney disease management. However, rather than focusing on day-to-day blood sugar levels, you need to aim for Hemoglobin A1c, a blood test that gives a view of your average blood glucose level over the past three months. The hemoglobin A1c target varies for different patients. For example, patients with early CKD should aim for a number lower than 7. However, in patients with advanced CKD patients and elderly patients, this target can be relaxed, shooting for a range between 7 and 8, because this population is at a higher risk of dropping their blood sugar levels dangerously low.

Control Your Blood Pressure

Controlling blood pressure is another key step in managing diabetic kidney disease. Once a diabetic patient shows protein in the urine, recommended target blood pressure is 110 systolic and 70 diastolic. Yet, here again, it is prudent to customize target blood pressure based on the patient’s age and other comorbidities. Since such tight blood pressure control carries the risk of reducing the pressure too low, which can be as harmful as high blood pressure, regular blood pressure monitoring before taking medicines is vital.

Although doctors have a long list of blood pressure medicines to choose from, certain drugs display remarkable kidney-protective profiles in addition to their blood pressure-lowering properties.

Kidney Protective Medications—ACEIs and ARBs

Although doctors have a long list of blood pressure medicines to choose from, certain drugs display remarkable kidney-protective profiles in addition to their blood pressure-lowering properties. This means that these medicines not only protect the kidneys of diabetic patients indirectly by lowering the blood pressure but also provide an additional layer of safety by directly making changes inside the kidney. These drugs are ACEIs and ARBs. ACEIs medications usually have -pril at the end of their names, as in Lisinopril and Ramipril. ARBs typically end with -tan, like losartan and Valsartan.

By reducing the diabetes-induced high-pressure state in the kidney’s blood vessels, these drugs slow down the ongoing damage, delaying the progression of kidney disease. However, kidney-protective medicines give their best when started early in diabetic kidney disease. In these patients, the same medication also prevents heart-related complications.

If you have diabetes, you must ask your doctor about these medications.

Note: Research showed that using both classes of drugs—ACEIs and ARBs—simultaneously puts you at high risk for adverse effects such as high potassium. Therefore, only one of the above two classes of drugs should be used at a time.

Newer Drugs—SGLT2 Inhibitors

Recently, a new class of drugs, SGLT2 inhibitors or Flozins, has emerged that sounds deceptively good for patients with diabetes. When a trial was studying one of these agents, empagliflozin, for its benefits on heart disease in diabetic patients, the drug showed unexpected outcomes, reducing the number of not only heart-related events but also kidney-specific abnormalities. Even better, all these benefits came while many patients were already on other kidney-protective drugs. This means the benefits of Flozins were in addition to the ones gained from ACEIs or ARBs. A later study focused explicitly on kidney outcomes of a similar drug, canagliflozin, replicated the same results, rapidly bringing this group of medicines into the limelight. Since then, study after study has confirmed their efficacy and safety.

Management of Diabetes in Advanced CKD

As diabetic patients enter the advanced stages of kidney disease, many of them are found pumping insulin to quell their raging sugar levels. Unfortunately, most physicians simply pass over two groups of sugar-lowering drugs and go on to insulin instead, even though these drugs are safe to use and have a broader benefit profile than insulin. These drugs help regulate sugar levels as well as improve kidney and heart health. These groups are DPP-4 inhibitors, such as Sitagliptin, and GLP-1 agonists, such as Liraglutide, both safe to use in advanced kidney disease.

This doesn’t at all mean that a patient should drop insulin entirely. Instead, insulin is a very helpful tool for diabetic patients with advanced CKD. But adding DDP-4 inhibitors and GLP-1 agonists provides benefits beyond just lowering blood sugar levels.

A Look into the Crystal Ball

Expect even more in the future. Modern medicine has already forayed into genomics and “omics,” techniques for developing new biomarkers of diabetic kidney disease. Genomics means the study of genes to identify genetic variants that influence the development of diabetic kidney disease. “Omics’ refers to techniques of protein and metabolite analysis in the blood and urine to identify and quantify these elements so that we can use them to predict and monitor the progression of diabetic kidney disease.

Take Home Message

Kidney disease is the most common small blood vessel complication of diabetes. Diabetic kidney disease accounts for a significant part of the CKD burden in the world. As a diabetes patient, you must understand the predisposition to kidney disease, its diagnostic tests, and the best available treatments.