A lesser familiar term in the world of kidney disease is “mineral bone disease.” Compared to other common concepts like salt and water balance, protein restriction and kidney function, the topic of mineral bone disease rarely comes into the discussion among CKD patients. Even if a kidney disease patient has never heard of the term, he must experience the symptoms: aching body and stiff joints, itching, dry skin, and shallow, tiring sleep. At its worst, mineral bone disease damages the bones and blood vessels.

These symptoms appear once failing kidneys can no longer maintain the balance of calcium, phosphorus, vitamin D, and parathyroid hormone. When the level of all of these components gets out of balance, your blood behaves like engine oil that was long due to being changed, and just as such oil is corrosive for your car, such blood is unhealthy for your bones and heart and blood vessels.

How Do You Arrive At Bone Disease

It all starts with the kidney’s decreasing ability to get rid of phosphorus from the body, even before you are aware of the kidney disease. Somehow, the body manages phosphorus levels within normal range throughout this period. However, as the kidney function declines further, things change. Its ability to produce an active form of vitamin D wane, which the body needs to absorb calcium from the food into the blood. Additionally, the kidney’s grip on phosphorus had become weak enough for phosphorus to rise above its normal range. The commotion created by this trio—high phosphorus, low vitamin D, and low calcium—provokes four small glands in our neck called parathyroid glands, stimulating them to produce copious quantities of parathyroid hormone. Higher levels of the parathyroid hormone manage to bring phosphorus, calcium, and vitamin D toward the normal range, but this kind of control comes at a cost.

How Bone Disease Affects the Organs

Parathyroid hormone forces kidneys to work harder to eliminate the excessive phosphorus, but with partial success. Next, the hormone targets our skeleton, moving calcium out of the bones into the blood, making them weak and brittle. By this time, parathyroid is not the only chemical that bothers the bones; failing kidneys accumulate other toxins in the blood, giving it a more acidic hue, another factor that leeches our skeleton.

These changes in the body result in achy bones and stiff joints. Skin becomes dry and itchy. Anemia worsens. Blood vessels become hard, choking the blood supply, which slows down the process of healing, escalating minor injuries or infections into amputations. Hardening vessels in the heart lead to weak heart muscles and even heart attacks.

Management of Mineral Bone Disease

To manage mineral and bone disease, a nephrologist regularly monitors your blood calcium, phosphorus, parathyroid hormone, and vitamin D levels, sometimes as frequently as every month.

Based on your labs and symptoms, your doctor uses a combination of dietary changes and medicines to slow down the progression of your kidney disease and soothe your symptoms.

Phosphorus Management

Toward the late stages of kidney disease, phosphorus becomes a nagging problem. Its level gets progressively higher as kidney function declines, requiring meticulous management.

Let’s first understand what does phosphorus management mean? Many, many years ago, doctors thought that the phosphorus levels of CKD patients should be the same as non-kidney disease patients. But forcing the phosphorus down to the normal range led to more problems than benefits. Rather than strengthing the bones, as doctors hoped, tight phosphorus control made the bones weaker and more prone to fractures. Nor did it show the expected benefits toward heart health. Later on, research actually favored slightly elevated phosphorus levels in the late stages of CKD, commenting that relaxed phosphorus levels were not only good for bone health but also a reflection of better nutrition.

Therefore, guidelines now avoid recommending any target blood phosphorus level but suggest keeping it toward the upper limit of the normal range.

Dietary Restriction

The cornerstone of phosphorus management is dietary restriction. All foods contain some phosphorus, but most phosphorus in the diet comes from processed and packaged foods. By eliminating these foods from your meals, you can make a huge cut in your phosphorus intake. Canned foods use additives rich in phosphorus to prolong their shelf life. The best way to identify these items is to find the letters “Phos” on the label. If you see these letters, avoid using that item.

In short, a kidney disease patient must decrease or eliminate frozen and packaged foods, processed meat, cold cuts, and canned items. Other common foods that contain high phosphorus include dark beverages (coca cola), chocolate, deli meats, hot dogs, crackers, premade meals, dairy products, and nuts.

Stage 5 and dialysis patients should take only 800 to 1000 mg or even less phosphorus daily.

Medications

If dietary restrictions don’t do the trick, doctors have, as they always do, pills for this problem, too. These pills bind the phosphorus in your food during its transit through the intestine, preventing it from entering the blood. Therefore, for these pills to work perfectly, you need to take them with your food. Not a very pleasant thing to do. Plus, these pills are usually huge, so big that their size earned the epithet of “Horse pills.”

There are two main classes of phosphate binders: calcium-containing and non-calcium-containing. There is only a slight difference between the efficacy profile. Since the former is cheaper, they are the first-line drugs. For CKD patients whose calcium level runs on the lower levels, calcium-containing binders can be used without the fear of raising calcium levels. However, for patients with calcium levels already hovering above the normal range, non-calcium-containing binders are the preferred choice.

Parathyroid Hormone Management

Parathyroid management starts with regulating blood phosphorus levels, a measure that proves powerful enough for managing most patients. However, as kidney disease advances, managing parathyroid hormone becomes more challenging, often requiring medical intervention. For this purpose, doctors have a host of medications. They start with simpler forms of vitamin D, ones that are available over the counter. But you may require more active forms of vitamin D, such as Calcitriol and the like. If these medications fail, a more potent drug called calcimimetic has to be used, named for its calcium-mimicking action of binding to the parathyroid gland, where it suppresses the release of parathyroid hormone. While this drug commonly appears on the prescription of a dialysis patient, it is rarely needed for non-dialysis CKD patients.

MBD and Osteoporosis—A Weak Combination

Patients with advanced kidney disease are more likely to fracture their bones compared to a non-kidney disease patient. These fractures are not just due to the weak bones caused by parathyroid hormone and acidic milieu. Some of these fractures, particularly in women, are due to another process called osteoporosis. When a patient has both CKD-related bone changes and osteoporosis, things get tough (but bones get weak). Treatment becomes a challenge; the drugs used to treat osteoporosis can actually have harmful effects on CKD-related bone disease. These patients need multispecialty care with close monitoring. Vitamin D is a safe choice. Exercise gives, however, the best boost to your weak, thin bones. The training with weights, such as weight machines and free weights, is even better.

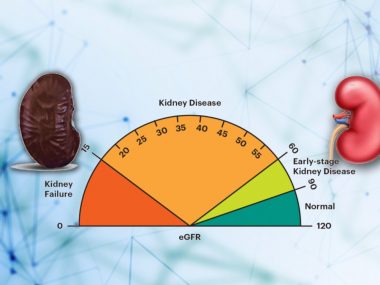

Acidosis

Acidosis, also called Metabolic acidosis, appears in about half of all CKD patients with eGFR below 30 ml/min. This acid is measured in the blood by using bicarbonate levels, reported on your blood test report as “CO2.” The worst the acidosis, the lower the CO2 levels. Acidosis can accelerate the loss of bone as well as kidney function. Healthy dietary changes like fresh fruits and vegetables greatly help, but most patients would need sodium bicarbonate pills taken three times daily.

A Misconception

Many patients believe dialysis lowers phosphorus and parathyroid hormone levels, so wouldn’t starting dialysis early be helpful? Dialysis does remove some phosphorus from the blood but not the parathyroid hormone, nor does starting dialysis early regulate the chemical cascade of mineral bone disease in any way. The best management of mineral bone disease involves dietary restriction and careful medical management, as outlined above.