Last week, while we were busy in our early morning rituals at the clinic, a patient walked in complaining of headache and dizziness. A young man, possibly in his early thirties, short in height, slim, and looking not very well. After his visit was over, I sat with my team and dissected the case, analyzing for them the metabolic syndrome, its many faces and various dimensions. Whether you are a patient or a healthcare worker, this case study might have a thing or two to make you a better surveyor of the metabolic landscape.

When the patient entered the main lobby and walked to our front desk, I was at my workstation. After his vitals were done and he was shown in the doctor’s office, I went over to my staff and asked about the patient’s vitals. Think of it as my habit of internal audit. The staff told me the patient’s numbers, all of which were normal except blood pressure, which was 154/95, and blood sugar, which was not checked. When asked why she did not check the patient’s blood sugar, the staff simply muttered her excuse. The omission, however, provoked my inner healthcare preceptor, triggering a long lecture on how with basic tools, like a blood pressure cuff and a glucometer, we can catch many manifestations of metabolic syndrome on a single visit, emphasizing particularly the significance of blood pressure and blood sugar as red flags for this silent epidemic. If used correctly and regularly, these tools can catch almost ninety percent of our metabolic syndrome patients at an early stage, allowing us timely medical interventions and lifestyle changes. This would benefit the patients not only by reversing hard vessels and spiking sugar. Ripples of such healthy lifestyle changes would go deep down to the level of genes, turning off bad genes and turning on the good ones.

Meanwhile, the patient came out of the doctor’s office. I asked him how much he understood about his condition, and, as patients usually do, he started over his story. A couple of days ago, he had a similar headache and dizziness while walking past Jinnah Hospital Lahore, a tertiary-level teaching hospital in Lahore. That day, he dragged himself into the emergency room, where, after being ignored for a few hours, he received an intravenous medicine for dizziness. After being ignored for another couple of hours, he walked away and went home. His vitals were never checked. Can you believe that! He stayed there for over 3 hours, he received a drug in his vein, and he never got his vitals checked! The visit to our clinic was his second episode of dizziness.

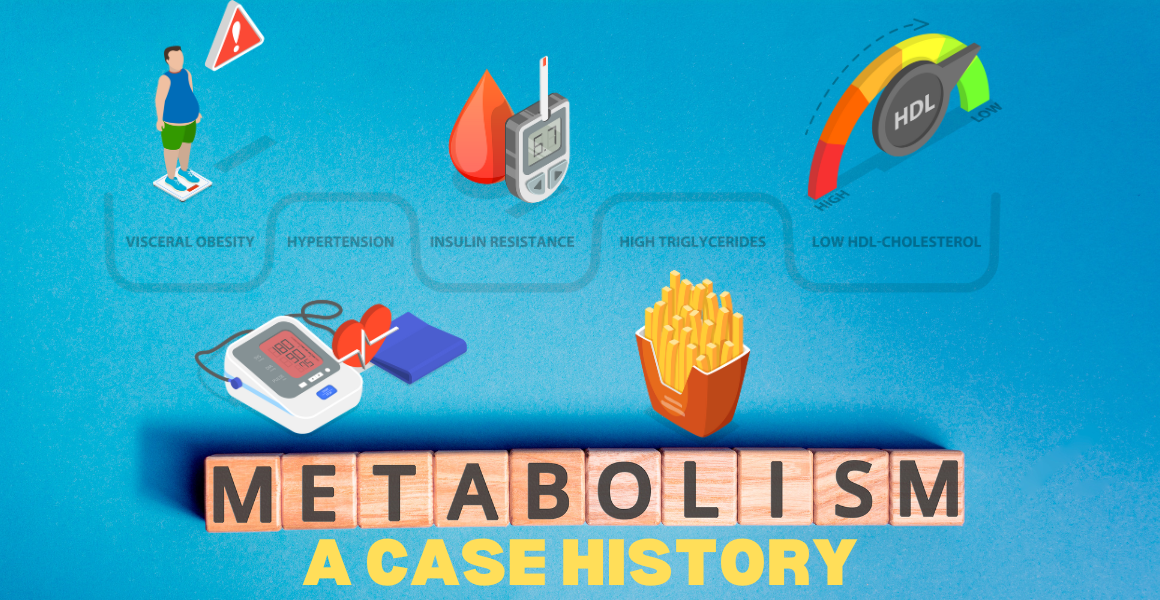

As the patient and I were chatting, my staff checked his blood sugar—154 one hour after breakfast, normal being less than 140. Now that I had his story and his basic vitals, I explained to him that he has both high blood pressure and possibly prediabetes and cautioned him not to take them as illnesses in themselves. These two anomalies mark something broader and deeper inside his body—metabolic syndrome, which results from insulin resistance, which, in turn, results from an unhealthy lifestyle.

Our discussion then moved on to lifestyle, and it turned out that this young man was living as unhealthy a lifestyle as a lower middle-class person could afford. He never did formal exercise. His sleep was short, superficial, and sketchy. His diet was far from healthy. And, of course, he carried the usual burdens of daily Pakistani stresses.

Simply put, we have a young man who has been unknowingly living an unhealthy life and, owing to this routine, having passed through various levels of insulin resistance, has now developed high blood pressure and possibly diabetes. This patient is not an individual case. He represents the vast majority of our youth that lives around us, carrying the burden of metabolic disturbances, well on its way toward cardiovascular kidney metabolic syndrome. And don’t even think for a moment that this is a problem of males alone. The situation of our female population is even worse. Remember that females account for a little over fifty percent of our total population, and more than ninety-five percent of these women live an unhealthy lifestyle. The vulnerability of this part of the population is absolute: our women hold little power over their circumstances; their days are mostly occupied with chores for others; they lack the equipment or freedom or will to exercise; they eat unhealthy and unnecessarily; their sleep is compromised due to their responsibilities; their mental health depends on the mental health of their father or brother or husband or son (though I’m afraid I have to disagree with it, but that is what they are taught).

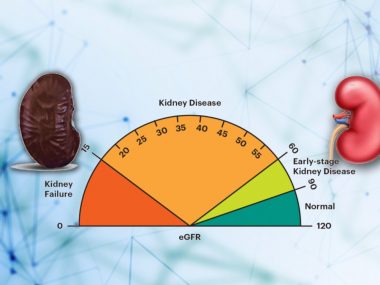

Back to the patient, I explained to him that he has been living an unhealthy lifestyle, putting him and his family at risk for serious health, financial, social, and mental crises. He should not think of his dizziness as an isolated event but as a landmark on his journey of worsening insulin resistance. His prediabetes confers that his liver and pancreas have already started to burn out. He should consider high blood pressure and elevated blood sugar as equivalent to road signs for danger ahead, warning about upcoming kidney, heart, brain, and eye injuries. And lastly, with high blood pressure, kidney health must be considered compromised until proven otherwise.

If we want to curb the upcoming metabolic crisis, we must prepare to deal with this clinical entity in its every form, from its silent, smoldering asymptomatic stage to its roaring, killing complications. We must begin with regular health checks and screenings and keep honing our clinical skills to use precise tests and the best medicines. And all of this doesn’t mean we should ignore artificial intelligence and the latest interventional techniques in dealing with the complexities of this multifaceted sickness. Given our attitude toward our health, the vast majority of our patients will still hit a healthcare door only after some symptom, and healthcare should not miss that golden opportunity.